Vaccines have been protecting us since the creation of the first small pox vaccine in 1796.1 However, the potency and protection of all vaccines can be compromised if appropriate vaccine storage and handling practices are not followed. Contamination, deterioration, and expiration of vaccines accounts for 19% of reports contributing to all vaccine handling.2 Data from the United States, Canada, Australia, and Western Europe during 2013-2014 showed that the influenza A/H1N1 strain was not effective due to extreme outdoor temperatures which caused vaccines to go beyond the recommended temperature ranges.3 While unfortunate, this may have been avoided with intentional vaccine storage and handling during transportation.

Vaccines have been protecting us since the creation of the first small pox vaccine in 1796.1 However, the potency and protection of all vaccines can be compromised if appropriate vaccine storage and handling practices are not followed. Contamination, deterioration, and expiration of vaccines accounts for 19% of reports contributing to all vaccine handling.2 Data from the United States, Canada, Australia, and Western Europe during 2013-2014 showed that the influenza A/H1N1 strain was not effective due to extreme outdoor temperatures which caused vaccines to go beyond the recommended temperature ranges.3 While unfortunate, this may have been avoided with intentional vaccine storage and handling during transportation.

The Risk of Vaccine Storage

Currently, improper storage temperatures have not been directly linked to consistent reports of significant harm or developing health risks, but links between vaccine storage and safety have been described.

In an evaluation of 476 reports of vaccine related adverse events, there were 33 adverse events related to a compromised vaccine being administered. Recipients receiving a compromised PPSV23 (pneumococcal polysaccharide 23-valent) vaccine accounted for approximately half of the 33 events reported, with 15 of the 16 reports being tied to one situation.

The most common reaction reported was local injection reactions with an occurrence rate of 66%. The remaining 12 adverse events were gastrointestinal anemia, dermatologic, or other infectious processes, and 1 case each of neurologic event, respiratory event, and death due to infection.11

However, at this time the key concern is not harm through an adverse event, but rather that an inadequate immune response may occur leaving the patient unprotected from the vaccine-preventable disease. To ensure that vaccine-preventable disease rates remain low, it is important that vaccines are stored at the recommended temperatures with event reporting if an excursion was to occur.6

Vaccine Storage & Handling Resources

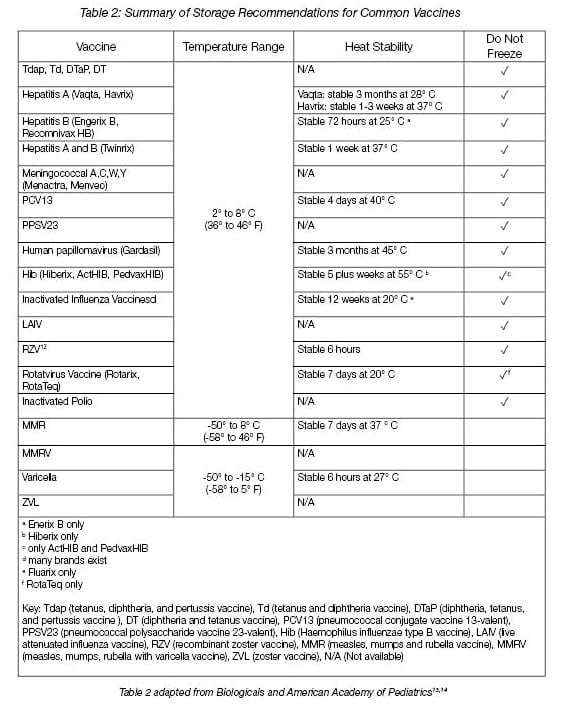

The CDC Vaccine Storage and Handling toolkit provides a thorough outline of vaccine storage and handling practices4. Additional resources on vaccine storage are also described in Table 1.

The Vaccine Cold Chain

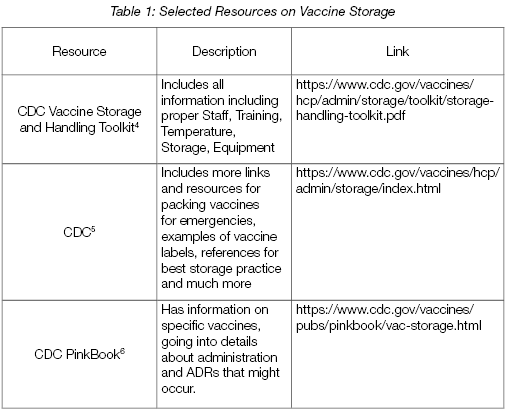

Specifically highlighted within the CDC Toolkit is the Vaccine Cold Chain. The Cold Chain encompasses the journey of the vaccine from the time it is manufactured to the time it is administered. A proper Vaccine Cold Chain consists of trained personnel, proper storage equipment, proper monitoring of storage temperatures, and proper temperature control during transportation.7

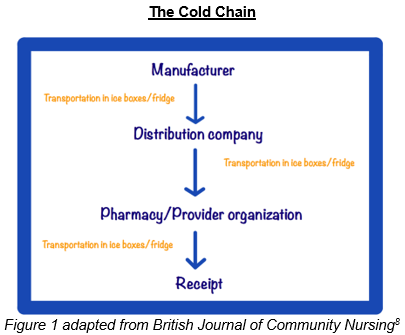

To maintain the Cold Chain, the CDC recommends that refrigerator temperatures should be maintained at 36° to 46° F and freezers should remain between -58° to +5° F.4,9 When temperature excursions occur, vaccines can become damaged which may result in reduced potency impairing the desired immunogenic response.9,10

Revaccination

The primary concern of improper storage is the patient acquiring a vaccine-preventable disease when they had expected robust protection. In order to circumvent development of vaccine-preventable disease when vaccine storage errors have been discovered, the CDC endorses revaccination. Revaccination with a properly stored vaccine ensures patients are adequately immunized. However, revaccination is time consuming and costly, and includes the risk that patients will be unwilling to get another dose leaving them susceptible to harmful disease. Other consequences and concerns include loss in confidence of provider, damaged reputations, financial burden due to wasted vaccines, and costs endured when replacing wasted vaccines.6

In 2017, 19% of 575 vaccine errors reported to ISMP VERP were due to storage concerns among vaccines.2 Unfortunately, not all storage errors are reported. Of note, there have been several facilities across the country implicated in recent years for temperature excursions necessitating revaccination efforts.

Two separate breakdowns in storage have been reported in California. One Medical Center notified 23,000 patients that revaccination was needed for all vaccines delivered in “faulty packaging”.16 Further south in California, 1,500 patients were affected by storage failure for influenza vaccines, with approximately half of those affected accepting revaccination.17

Several months later 1,600 patients in Indiana were discovered to be vaccinated with improperly stored vaccines and were offered revaccination. In most recent events, over a 13 month period, a clinic in Oklahoma provided 117 polio, meningococcal disease, and human papillomavirus vaccinations which had been stored inappropriately.16 In total, these four events add up to over 26,000 cases of improperly stored vaccines being administered within a 16 month period.

Emergency Storage Plans

Unforeseeable events such as natural disasters impact vaccine storage. While hurricanes, and to some degree blizzards, give advanced warning, oftentimes tornados, earthquakes, or unrelenting summer storms do not. Healthcare providers should not only implement proper vaccine storage daily but should also have plans for vaccine handling during natural disasters.

It is important for any facility to have a backup generator. Storage in a running refrigerator will keep the vaccine from losing its potency, so having a generator that will keep the temperature of the fridge constant is crucial. If the power outage is longstanding, it is also important to have a backup facility ready to transport the vaccines if need. It is important to train all staff responsible for removing the vaccines from the fridge, transporting, and restocking the vaccines in the backup facility. The proper equipment, such as special coolers and gloves, used during this process should also be preplanned and arranged before a disaster hits.4,9

Luckily no one is alone in dealing with the complexities and infrequent occurrences of improper vaccine handling. In addition to the online CDC Storage and Handling Toolkit, additional resources are available for guidance. Vaccine manufacturers can be contacted over the phone for questions about their specific vaccine storage requirements and any questions about noted changes. Impact on safety, efficacy and potency is often not visible, thus if a temperature excursions occurs it is important to contact manufacturers for further instruction.6 Local and State Health departments can also be useful in preparing an action plan for the facility and dealing with the aftermath of a natural disaster.18 Lastly, if a breakdown in storage does occur, the incident can be reported to ISMP VERP and Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS).19, 20

Other Blogs you may be Interested In...

- A Look into the 2019-2020 Flu Season

- Where to Properly Place a Temperature Probe in Your Vaccine Refrigerator

- The Ultimate Guide to CDC Vaccine Storage and Temperature Monitoring

- How to Handle Temperature Excursions: CDC Vaccine Storage & Handling Recommendations

- CDC Vaccine Storage and Handling Toolkit 2019: Refrigerator and Freezer Recommendations

Conclusion

Vaccines are essential for public health. As vaccine providers, it is our job to ensure vaccines are stored and handled safely throughout the entire cold chain (from manufacturing to administration). Tools and resources, such as the CDC Toolkit, are available to help providers carefully and thoughtfully store and handle vaccines. In addition, an investment in proper storage equipment, such as pharmaceutical-grade refrigerators, helps facilities keep vaccines stored at optimal temperature. It’s important to train and plan in advance for unexpected events so your vaccine supply is not at risk. It is our job to protect and care for our patients! For more information on proper storage according to the CDC Best Practices, view the Ultimate Vaccine Guide below.

References:

- Darmon P. [The beginnings of vaccine diffusion in France (1800-1850)]. Bull Acad Natl Med [Internet]. 2001 [cited 2019 Aug 21];185(4)767-76. English, French. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11503362.

- ISMP National Vaccine Errors Reporting Program 2017 analysis (part 1): vaccine errors continue with little change. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. https://www.ismp.org/resources/ismp-national-vaccine-errors-reporting-program-2017-analysis-part-i-vaccine-errors. Published Jun 14, 2018. Accessed: Aug 21, 2019.

- Caspard H, Coelingh KL, Mallory RM, Ambrose CS. Association of vaccine handling conditions with effectiveness of live attenuated vaccine against H1N1pdm09 viruses in the United States. Vaccine [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Aug 20];34(42):5066-72. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.08.079.

- Storage and handling toolkit. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/admin/storage/toolkit/index.html. Updated Jul 11, 2019. Accessed: Jul 30, 2019.

- Storage and handling resources. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/admin/storage/index.html. Updated Jul 11, 2019. Accessed: Aug 22, 2019.

- Chapter 5: storage and Handling. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/vac-storage.html. Updated May 16, 2018. Accessed Jul 31, 2019.

- National vaccine storage and handling guidelines for immunization providers 2015. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/national-vaccine-storage-handling-guidelines-immunization-providers-2015.html#a1a1. Published Dec 14, 2015. Accessed Aug 22, 2019.

- Armstrong K. Safely administering and storing vaccines in the community setting. Br J Community Nurs [internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Aug 23];22(9):422. Available from: https://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/pdf/10.12968/bjcn.2017.22.9.422.

- Vangroenweghe F. Good vaccination practice: it all starts with a good vaccine storage temperature. Porcine Health Manag [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Aug 1];3(24):1-7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5713130/pdf/40813_2017_Article_71.pdf

- Temperature sensitivity of vaccines. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/69387/WHO_IVB_06.10_eng.pdf;jsessionid=C1F8DEFDDCF1E7E0AE9163EFC0C7F811?sequence=1. Published Aug 2006. Accessed Aug 19, 2019.

- Hibbs BF, Miller E, Shi J, Smith K, Lewis P, Shimabukuro TT. Safety of vaccines that have been kept outside of recommended temperatures: reports to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), 2008-2012. Vaccine [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Aug 1];36(4):553-58. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.11.083.

- Shingrix storage and handling. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/shingles/hcp/shingrix/storage-handling.html. Updated Jan 25, 2019. Accessed Aug 25, 2019.

- Kumru OS, Joshii SB, Smith DE, Middaugh CR, Prusik T, Volkin DB. Vaccine instability in the cold chain: mechanisms, analysis and formulation strategies. Biologicals [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2019 Aug 7];42(5):237-59. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biologicals.2014.05.007.

- Vaccine Storage Chart. American Academy of Pediatrics. https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/immunizations/Practice-Management/Pages/vaccine-storage-chart.aspx. Updated Feb 2019. Accessed Aug 26, 2019.

- Poland GA. Influenza vaccine failure: failure to protect or failure to understand? Expert Rev Vaccines [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Aug 1];17(6):495-502. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6330882/pdf/nihms-1514615.pdf.

- Rodriquez CH. Vaccine storage too often fails to meet standards. Kaiser Health News. https://khn.org/news/vaccine-storage-too-often-fails-to-meet-standards/. Published Feb 12, 2019. Accessed Aug 17, 2019.

- Steele J. San Diego VA’s haywire alert system led to bad flu vaccine, ‘accountability’ actions underway. San Diego Union Tribune. https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/military/veterans/sd-me-va-pharmacy-vaccine-problem-20171213-story.html. Published Dec 13, 2017. Accessed Aug 17, 2019.

- Where to go. Vaccines.gov. https://www.vaccines.gov/getting/where. Updated Jan 2018. Accessed Aug 26, 2019.

- Hibbs BF, Moro PL, Lewis P, Miller ER, Shimabukuro TT. Vaccination errors reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) United States, 2000-2013. Vaccine [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2019 Aug 26];33(28):3171-78. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.006.

- Error reporting for consumers. Institute for safe medication practices. https://www.ismp.org/report-error/consumer. Accessed Aug 26, 2019.

Contributing Authors

Maria Jasser

Maria Jasser is a native of Birmingham, Alabama. She completed her undergraduate prerequisites for pharmacy school at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. She will graduate with her Doctor of Pharmacy degree in May 2020 from the Harrison School of Pharmacy at Auburn University.

Ashley Flowers

Ashley Flowers is a native of Pensacola, Florida. She graduated from the University of West Florida with her Bachelors Degree. She will graduate with her Doctor of Pharmacy degree in May 2020 from the Harrison School of Pharmacy at Auburn University.